Margaret Calvert & Jock Kinneir

In 1950 the UK had four

million licenced vehicles. By 1970 that reached almost ten million and half of

UK households had access to them. The increase in car ownership meant that

pre-existing roads were inadequate, leading to the building of the UK’s first motorway

in 1958. While it was been planned and

built, it was realized that current road signs may be hard to read at the high

speeds possible on the new motorway. A system of new signs was needed. The job

of designing the signs for UK’s motorways was given to duo Margaret Calvert and Jock Kinneir, and the project

later led to the re-design of every road sign on Britain’s roads. This duo is

responsible for much of Britain’s visual identity in the 20th

century and helped millions find their way across the country, as well as in

every railway station, airport, and hospital.

Richard “Jock” Kinneir

Born in Hampshire

in 1917, Jock was student of Chelsea School of Art, specializing in engraving.

After World War II he worked for the Central Office of Information as an

exhibition designer. Then, he worked for the Design Research Unit from 1950-56,

before starting up his own practise in 1952. In 1954 he began teaching design

part-time at Chelsea School of Art, which is where he first met Margaret. In

1957, thanks to a chance meeting with architect David Alford at a bus stop, he received his first commission - to design

the signage for Gatwick Airport. He

later became head of the graphic design department of The Royal College of Art

in 1964 and wrote Words and Buildings in 1980. He died in 1994.

Margaret Vivienne Calvert

Born in South Africa in 1936, Margret came to England in

1950. She studied illustration at Chelsea School of Art before been invited by Jock to join him on designing the signage for Gatwick

Airport in 1957.

“I studied for four years at Chelsea and graphic design

didn’t exist at that time. I think they called it “commercial art.” And I just

love doing life drawing and talking to fine artists. It was marvellous after

school to have that freedom. So, Jock Kinneir came in one day to introduce the

illustrators and bookmakers to what he would call design and he set us a

project that involved hand lettering. And I was just hooked from then on.” - Margaret

Calvert

Their First Collab at Gatwick

Jack and Margaret’s first collaboration was for the signage

for Gatwick Airport in 1957. Been their first job, it was a big learning curve

which shaped their later work. At the time, Margaret enrolled in evening

classes on typography at the Central School of Arts & Crafts, and got her

first independent gig designing the front of Schweppes soda vending machines in

West London.

“Jock got that job almost by chance. He had a neighbour

called David Alford from Yorke, Rosenberg & Mardall, and they were

designing Gatwick. It was a big prestige project as you can imagine. They were

in the same queue waiting to get the Green Line bus to Hyde Park Corner, and

David said, 'We've got this job, and we need someone to do signs, are you

interested?', so Jock said 'Of course', although he knew very little, if

anything about signing large buildings. I had just taken my final exams when he

invited me to work for him.” - Margaret Calvert (Frieze, 2003)

The P&O Route

Inspired by a magazine article about Gatwick’s signage, the

design-conscious chairman of P&O shipping Colin Anderson commissioned Jock

to design luggage labels for his passenger services. In that same year he

became chairman of the government committee formed to design the UK’s first

motorways, which is probably how Jock got the road sign gig.

“Intended for use by sometimes illiterate labour, the

labels are coded visually: shape of label indicates place of storage on board,

colour indicates the area of the world to which the baggage is destined,

pattern shows the port of off-loading in that area.” - Kinneir Calvert Tuhill

brochure (1971)

“That’s my first attempt at drawing lettering because that

kind of typeface just didn’t exist’. - Margaret Calvert

Road Signs Before Jock and Margret

Before 1964 road signs in the UK were a disorganised mess. Modern

signage began as a by-product of the popularity of bicycles. Cyclists (like

motorists) needed warnings of hazards on unfamiliar roads. In the 1880s cycling

organisations were erecting cast-iron “danger boards” and, in 1888, the

government (through county councils) were pressured into been responsible for

the roads, leading to the semi-standardized implementation of direction signs

and milestones.

The story repeated when cars gained popularity. Motoring

organisations erected their own warning and direction signs. A standardized

system of two signs on one post was produced from the Motor Car Act of 1903,

becoming the standard used from 1934. But national specifications were

advisory. Although symbols were used on signs in Europe from 1909, the British

dismissed the idea and sticked to worded signs until a review in 1921 changed

their mind. Symbols plus words were the norm then on.

During World War II, direction signs were blacked out or

removed to hinder possible German invasions. After the war, the motoring

organisations, like the AA and the RAC, erected non-standard “temporary” signs.

Also, signs began to look similar to those found in Europe.

However, the Worboys Committee report of 1963 listed the

following flaws with that signage –

“(a) roadside signs are too small to be readily

recognisable as such and to be easily read by drivers travelling at the normal

speed of traffic;

(b) they do not have a simple, integrated appearance;

(c) the more important signs are not readily

distinguishable from the less important at long range;

(d) they are often not effective at night;

(e) they are different from those used on the continent of

Europe and only those who can read English can fully understand them;

(f) they are often mounted too high, particularly in rural

areas;

(g) they are often badly sited in relation to junctions;

and

(h) there is insufficient continuity of place names on

directional signs.”

The UK’s First Motorway (Signs)

As the UK’s first motorway was been developed, in 1957 the

government set up an advisory committee with Colin Anderson as chair and MoT

civil servant T. G. Usborne in charge of proceedings. They had America and

Germany’s signage, prior research by the Road Research Laboratory, and advice

from nearly 30 organisations to go by. Wanting their signs to be the best ever

designed, committee member Hugh Casson initially suggested a collaboration with

the Royal Collage of Art (where Hugh was a professor. Eventually, the committee

commissioned Jock and Margaret to design the UK’s motorway signage system.

When the duo looked at Germany’s Autobahn signage, they had

a thought – we can do better than that. To Margaret “The signs were all in

upper and lowercase letters. Very aggressive and fairly ugly and uncompromising

because they were designed by engineers.” And so, they began designing their

own signs and typeface for them.

Testing the typefaces and letter spacing involved “a lot of

squinting.” They tested their signs in an underground car-park in Knightsbridge

to simulate night-time conditions. They also tested signs in Hyde Park,

propping prototypes up against trees, and walking towards them slowly. They

were then placed on a car and driven by committee member, former racing driver,

Lord Waleran as fast as possible on the runways of RAF Hendon. Finally, the

first signs were installed on unopened stretches of Preston Bypass and M1, with

testers in police cars going 90mph. The Preston Bypass opened on 5th

December 1958 and the first section of the M1 opened on 1st November

1959 – using Jock and Margaret’s signs. The Times said that they were “a

complete breakaway from present British usage”.

Jock later recalled the moment he realized his signs really

worked. One evening, after a committee meeting in the north of England, Lord

Waleran offered in a lift back to London in his Jaguar. As Waleran drove down

the M1 at 95mph, Jock was “delighted to see the signs were legible when one was

doing that speed at night.”

To begin with, because of their large size, the signs backs were painted dark grey-green to make them less conspicuous.

What about the rest of the Road Network

In 1961 designer Herbert Spencer drove from Marble Arch to

Heathrow Airport and photographed every road sign he came across. The result was

a photo essay published in his graphic design magazine Typographica.

Headlined “Mile-a-minute typography.” Herbert said that there was “an urgent

need to review the whole system of British road signs and specially to adopt

simple pictorial symbols in place of the wordy and often ambiguous notices at

present in use”.

In response to Spencer’s lobbying, the government set up an

advisory committee, chaired by Walter John Worboys (from ICI) in July 1963 to

review signage on all British roads. T. G. Usborne was in charge of proceedings

again, and (with the success of the motorway signs) Jock and Margaret were commissioned

again to design new signs.

So, they started again. Like they did for the motorway

signs, they looked at pre-existing signs in Europe and thought “we can do

better.”

The resulting work was filtered back into the motorway

signs they previously designed, resulting in a few changes to make them

consistent with the new non-motorway signs. The new sign system became law in

1965.

Symbols from Life

“We’d always seen Britain as very literate, so having

pictures on signs, which was more European, was seen as a big change.” - Margaret

Calvert (Daily Mail, 2004)

“Pictograms? It’s easier to learn English.” – Jock Kinneir,

on how symbols can be open to interpretation in multiple ways by different

people.

Although UK signs had used pictograms before, they just

grabbed the driver’s attention to the sign’s text. Pictograms only signs were

the biggest change to the system. When it came to designing the pictograms,

Margaret took inspiration from her own like. The cow on the sign warning

drivers of farm animals on the road, for example. “My main model was a cow

called Patience that my farmer relatives had in Wiltshire.”

“There were pictograms of children on European signs, but

they were often crudely drawn by engineers. There were some illustrated school

signs in England, but they used to be of a boy of about ten with a satchel and

a cap, and a small girl behind him. It was quite archaic, almost like an

illustration from Enid Blyton, and very grammar-schooly. I wanted to make it

more inclusive because comprehensives were starting up, and I didn’t want it to

have a social class feel. … I switched it to make the girl more caring, with

her leading a little boy. My model for the girl was myself as a child –

although I was very skinny as a girl, so I beefed myself up a bit because you

have to draw a shape that can be seen from a distance.” - Margaret Calvert (Daily

Mail, 2004)

“I just wish I’d left the tip on it to show it was a

shovel.” - Margaret Calvert

Business Partners

Jock’s company, Kinneir Associates, moved into a small

rented office above a garage in Knightsbridge in 1956. This is why most

tellings of Jock’s life say “he stated his own business in 1956.” The company

was renamed Kinneir Calvert & Associates in 1966, when Margaret officially

became a partner.

In 1970 it had become Kinneir Calvert Tuhill Ltd, when David

Tuhill joined as a partner. He became a partner because he “represented more

clearly a strand of graphic design that had come to predominate in London, and

with which Jock Kinneir never felt much affinity: a frankly commercial,

‘ideas’-based graphics that employed sharp copywriting and slick illustration

or photography.”

After the road sign gig, Jock and Margaret worked on

signage for the rebranding of British Rail in 1965, signs for NHS hospitals, a

few airports (including Glasgow’s, which included a Saltire-inspired logo), and

the armed forces. Their last collaboration was the Tyne & Wear Metro in

1977.

Post-Jock Margaret

Margaret has always been an independently minded creative,

with multiple creations made during her time as assistant and, later, business

partner to Jock. In 1978 she won a D&AD Silver award for book the

typography in David Hockney’s book Travels with Pen, Pencil and Ink. After Jock

retired in 1980, she started her own practice.

She taught at the Royal College of Art and was head of

their Department of Graphic Arts and Design from 1987-91. She became a senior

fellow in 2001. She was awarded an honorary fellowship by University of the

Arts, London, in 2004.

Despite her vast repertoire, her work on road signs is the thing most people remember her for - and she has used that in her own work, exemplified by her typeface A26, created for Neville Brody’s Fuse project in 1994.

MoT Logo

In 1960 the Ministry of Transport introduced the annual MoT

test to test the road-worthiness of old cars. “Jock designed the MoT symbol and

the three triangles reflect the three parts of the test as it was then carried

out [brakes, lights and steering].” - Margaret Calvert (Frieze, 2003)

Burkett/Rudman fishmongers (1962)

Glasgow Airport (1964)

“What do I want to know, trying

to read a design at speed?”- Jock Kinneir

“Style never came into it. You were driving towards the

absolute essence.” - Margaret Calvert

The Geneva Protocol

In 1949 the Geneva Convention on Road Traffic took place,

setting up an international standard for road signs. If Jock and Margaret had a

strict design brief for the UK’s road signs this was it.

Danger Signs

“The danger signs shall be in the shape of an equilateral

triangle with one point upwards except in the case of sign "PRIORITY ROAD

AHEAD" [GIVE WAY] which shall have a point downwards.”

“These signs shall have a red border with white or

light-yellow ground. Symbols shall be black or dark.”

Instruction Signs

“The signs of this class shall be circular in shape.”

Probibitory Signs – speed limit

“Except where otherwise specified or shown in the diagrams

of this Protocol, the colours of prohibitory signs shall be as follows: white

or light yellow, with a red border, the symbol being black or of a dark

colour.”

Mandatory Signs – cycle lane

“The colour of mandatory signs shall be as follows: blue

ground with a white symbol.”

Informative Signs

“The signs of this class shall be rectangular in shape.”

“Where the colours to be used are optional, the colour red

shall in no case predominate.”

Advance Direction Signs

“The advance direction signs shall be rectangular in

shape.”

“Their size shall be such that the indication can be

understood easily by drivers of vehicles travelling at speed.”

“These signs shall have either a light ground with dark

lettering or a dark ground with light lettering.”

Direction Signs

“Direction signs shall be rectangular with the longer side

horizontal and shall terminate in the form of an arrowhead.”

“Names of other places lying in the same direction may be

added to the sign.”

“When distances are indicated, the figures giving

kilometres (or miles) shall be inscribed between the name of the place and the

arrow-head.”

“The colours of these signs shall be the same as those for

advance direction signs.”

Place and Route Identification Signs

“Signs indicating a locality shall be rectangular in shape

with the longer side horizontal.”

“These signs shall be of such a size and placed in such a

manner that they shall be visible even at night.”

“These signs shall have either a light ground with dark

lettering, or a dark ground with light lettering.”

“Since

cost-effectiveness was our criterion, it was evident that we would have to work

in terms of minimum preferred dimensions between units. Once again, it was the

scientists who put the necessary tool in our hands. They suggested that we use,

as a unit of measurement, the width of a letter stroke, e.g., the capital “i”.

In this way the dimensions would remain proportionally the same even if the

size of the letter changed. The implication of this thinking was that any

graphic element which did not prove itself necessary should be eliminated. We,

therefore, disposed of arrow heads on road symbols and ruled boxes around groups

of names. Seeing these appendages go was like taking a stone out of one’s shoe

as well as giving us greater flexibility in layout and a greater truth to

geography.

The

latter was the fundamental factor. It dictated that, wherever possible,

map-type signs depicting the actual layout of road junctions would be preferred

to signs using stacks of names and arrows.

The

stack-type signs would be used only when there was not enough space in which to

erect the larger map signs.” - Jock Kinneir (Transportation Graphics: Where Am I Going? How

Do I Get There? - The Museum of Modern Art, 1967)

“We found it considerably cheaper to reflectorize white

words and symbols on a dark ground rather than on the reverse. When, however,

local destinations or minor roads are involved, the signs are inevitably

smaller; therefore, it is necessary to have a white sign in order to insure

conspicuity. This physical requirement was utilized to express the grading of

the roads and was, in part, responsible in determining the need for two

alphabets of different weights. The other reason being the halation effect of

the reflective material. White letters have to be lighter in weight than black

ones for similar performance.” - Jock Kinneir (Transportation Graphics: Where Am I

Going? How Do I Get There? - The Museum of Modern Art, 1967)

Which Colour?

“The scientists then advised us that white letters on a

colour in the blue—green range were most legible and a wrangle over the exact

choice of colour ensued which was lengthy and at times impassioned. Black,

everyone agreed, was too funereal; very dark blue was found often to look

black. Since the scientists had advised that blue should be reserved for

motorways, the hue had to be green. The argument, then, polarised between our

demand for a bright green which every man could recognize and name as such and

the architects’ demand for a green which was nearly black (‘the blacker, the

better’). Our opinion was that their choice conformed to an ‘in-taste’ and was

unrealistic. While this argument raged, the Laboratory made some signs for

testing in a mid—green of their own choosing. These signs were erected at

Slough near London and the colour finally used came to be known as Slough

green. Initially, we opposed the selection on subjective grounds; however, we

feel now that it has some merit.” - Jock Kinneir (Transportation Graphics: Where

Am I Going? How Do I Get There? - The Museum of Modern Art, 1967)

In the UK, signs

on motorways are blue. On primary routes their green. White is used on for minor

roads and in settlements. Yellow is used to sign non-permanent situations, such

as diversions. Additional colours can be used of specific situations. For

example, purple signs were used around Glasgow to mark out a “Games Route

Network” for athletes and officials to use during the 2014 Commonwealth Games.

Committee member

Hugh Casson played a role in the green decision, thinking it should be dark

green “like the colour of old dinner jackets.” The first “Slough green” signs

were set up at the A34 at Hall Green, Birmingham, in 1963.

Originally the

committee decided on green for the motorway signs, because they thought it

would be the “most distinctive colour” and “would at the same time give good

contrast.” But they changed their minds to blue when they saw blue used in

Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. Also, blue would stand out “against the

natural greens of the countryside”.

The Transport Medium “I” stroke width is the yardstick for the whole sign system. Borders are 1.5 strokes wide. Route arms on junction map signs are 2.5, 4, or 6 strokes wide (depending on their status) and gaps between two unrelated blocks of text is 12 strokes wide.

Transport Typeface

“I am anxious you shouldn’t embark upon inventing an alphabet of a character quite “new”. We have, as a committee, got into the habit of accepting the general weight and appearance of the German alphabet as being the sort of thing we need! I think therefore something on those lines is what the Committee believes it wants…’ Colin Anderson (Letter dated 26th June 1958).

Seeing the “German alphabet” as effective, but ugly for British taste, the duo ignored this request and designed a new typeface. Based on Aksidenz Grotesk, Transport is softer and curvier than the blunt modernist typefaces used on signs on continental Europe, making it seem friendlier and appealing to British drivers. The committee liked it and got “Almost unanimous” support from consultive organisations.

This is DIN 1451, the typeface used on German road signs since the1930s. Its designed to be drawn precisely, using any drawing instrument, with the help of a compass, ruler and grid. No wonder it looks “mathematical and monotone.”

Transport’s letters are designed to be made into tiles that can be resized for signs in any size and ensure correct spacing between the letters at the same time.

“The basis of the letter design was the need for forms not to clog when viewed in headlights at a distance. For this reason, counters [the spaces within letters, such as “a” and “c”] …. had to be kept open and gaps prevented from closing. Also, as pointillist painting has shown, forms tend to merge when viewed from a distance, and this suggested a wider letter spacing than is usual in continuous text.” - Jock Kinneir

Transport Heavy was created for white signs, because at night the halo created by the reflective coating would make black Transport Medium text harder to read. White Transport Medium text appeared bolder with the halo on blue motorway signs.

The original version of Transport was digitized and released by URW Type Foundry in 2001. These words are written in this form of Transport.

In 2008 K-Type introduced an unofficial “redrawing” of Transport - Transport New. Its main application has been the typeface for the interface of video game Untitled Goose Game, a game set in an idyllic English village.

Transport goes Online

When Ben Terrett and his Government Digital Service design team got the task of revamping the British government’s official website one requirement is that it had to be as accessible as possible. So, they needed a typeface that is easily readable. But one that was also British was preferable. So, they chose Transport. To be more precise New Transport, designed by Henrik Kubel and Margaret. This version came in seven weights and included italics, as well as small capital letters and Eastern European characters. It was released by A2 Type in 2012.

"It is really exciting to see New Transport used for the first time, online, for the Government’s website... Almost as exciting as driving down the M1 for the first time." – Margaret Calvert

GOV.UK went online in 2012, and it proved so good a design that it became overall winner of the 2013 Design Museum’s Design of the Year Award. Since 2013, every time someone in the UK needed to use a government service digitally, did so through GOV.UK on a page typeset with New Transport.

Motorway Typeface

Jock and Margaret designed two typefaces for use on motorways back in 1958. This second “typeface,” Motorway, isn’t a complete character set, which may be why most typeface history books don’t bother mentioning it. It didn’t need a complete set, because its only purpose is to label route numbers on signs on, or pointing to, motorways.

It comes in two variants – “Permanent,” used on blue motorway signs.

“Temporary,” a bolder version used on yellow temporary signs.

K-Type digitized it, creating a complete character set for it, in 2015. Their version comes in three weights – Bold (Temporary), SemiBold (Permanent) and (new) Regular – and comes in italics.

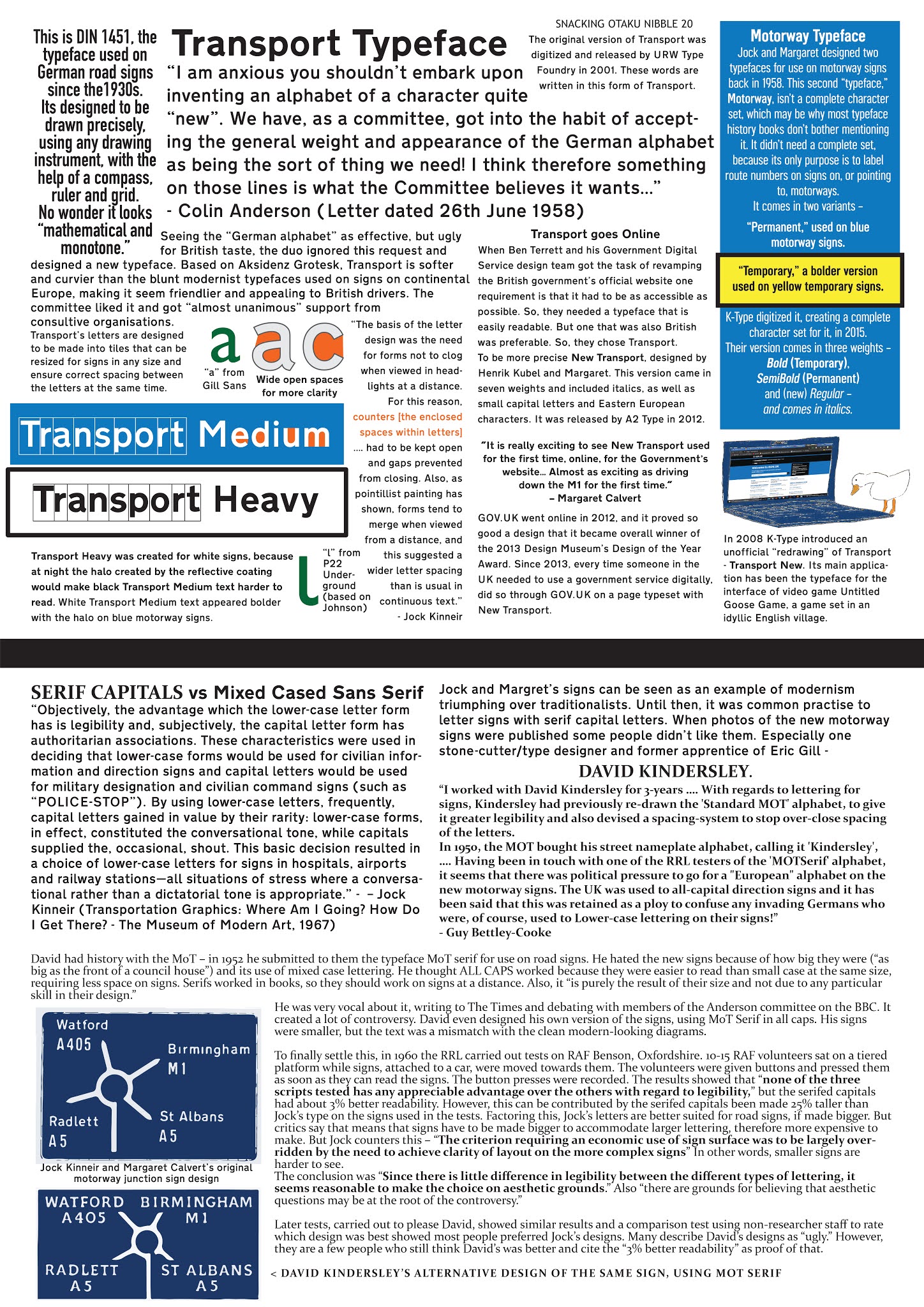

Serif Capitals vs Mixed Cased Sans Serif

“Objectively, the advantage which the lower-case letter form has is legibility and, subjectively, the capital letter form has authoritarian associations. These characteristics were used in deciding that lower-case forms would be used for civilian information and direction signs and capital letters would be used for military designation and civilian command signs (such as “POLICE-STOP”). By using lower-case letters, frequently, capital letters gained in value by their rarity: lower-case forms, in effect, constituted the conversational tone, while capitals supplied the, occasional, shout. This basic decision resulted in a choice of lower-case letters for signs in hospitals, airports and railway stations—all situations of stress where a conversational rather than a dictatorial tone is appropriate.” - – Jock Kinneir (Transportation Graphics: Where Am I Going? How Do I Get There? - The Museum of Modern Art, 1967)

Jock and Margrett’s signs can be seen as an example of modernism triumphing over traditionalists. Until then, it was common practise to letter signs with serif capital letters. When photos of the new motorway signs were published some people didn’t like them. Especially one stone-cutter/type designer and former apprentice of Eric Gill - David Kindersley.

“I worked with David Kindersley for 3-years …. With regards to lettering for signs, Kindersley had previously re-drawn the 'Standard MOT' alphabet, to give it greater legibility and also devised a spacing-system to stop over-close spacing of the letters.

In 1950, the MOT bought his street nameplate alphabet, calling it 'Kindersley', …. Having been in touch with one of the RRL testers of the 'MOTSerif' alphabet, it seems that there was political pressure to go for a "European" alphabet on the new motorway signs. The UK was used to all-capital direction signs and it has been said that this was retained as a ploy to confuse any invading Germans who were, of course, used to Lower-case lettering on their signs!” - Guy Bettley-Cooke

David had history with the MoT – in 1952 he submitted to them the typeface MoT serif for use on road signs. He hated the new signs because of how big they were (“as big as the front of a council house”) and its use of mixed case lettering. He thought ALL CAPS worked because they were easier to read than small case at the same size, requiring less space on signs. Serifs worked in books, so they should work on signs at a distance. Also, it “is purely the result of their size and not due to any particular skill in their design’,

He was very vocal about it, writing to The Times and debating with members of the Anderson committee on the BBC. It created a lot of controversy. David even designed his own version of the signs, using MoT Serif in all caps. His signs were smaller, but the text was a mismatch with the clean modern-looking diagrams.

To finally settle this, in 1961 the RRL carried out tests on Benson Airfield, Oxfordshire. 10-15 RAF volunteers sat on a tiered platform while signs, attached to a car, were moved towards them. The results showed that “none of the three scripts tested has any appreciable advantage over the others with regard to legibility,” but the serifed capitals had about 3% better readability. However, this can be contributed by the serifed capitals been made 25% taller than Jock’s type on the signs used in the tests. Factoring this, Jock’s letters are better suited for road signs, if made bigger. But critics say that means that signs have to be made bigger to accommodate larger lettering, therefore more expensive to make. But Jock counters this – “The criterion requiring an economic use of sign surface was to be largely overridden by the need to achieve clarity of layout on the more complex signs” In other words, smaller signs are harder to see.

The conclusion was “Since there is little difference in legibility between the different types of lettering, it seems reasonable to make the choice on aesthetic grounds.” Also “there are grounds for believing that aesthetic questions may be at the root of the controversy.”

Later tests, carried out to please David, showed similar results and a comparison test using non-researcher staff to rate which design was best showed most people preferred Jock’s designs. Many describe David’s designs as “ugly.” However, they are a few people who still think David’s was better and cite the “3% better readability” as proof of that.

Serif letters are characterized by their high contrast of thick and thin strokes, which, quoting Anderson committee member Noel Carrington, from a letter to the editor of The Times in 1959, “would almost certainly prove unsuitable when the letters have to consist of reflectionized material to catch the headlights.”

Rail

Alphabet

“January

1965 marks the start of an entirely new look for British Railways. All parts of

the system will be given a recognizable house style. The Main elements are a

new symbol, new livery and new letter styles.” – The new face of British

Railways poster (1964)

In 1964

the Design Research Unit was commissioned to given the nationalized British

Railways a new co-ordinated modern identity. This included a name change

(shorted to British Rail), Gerry Barney’s “double-arrow” logo, company colours

and a new typeface.

When

given the job for signs for British Rail, Jock originally thought of just

reusing Transport. It was tried out in Coventry in the early-1960s. But it was

soon realized that Transport, designed to be read by fast-moving drivers, was

surplus to requirements. Rail passengers walked slowly, so they had more time

to read signs. So, the duo revisited Gatwick Airport and modified the typeface

they used there, resulting in Rail Alphabet.

Rail Alphabet’s letters are slightly heavier and

more closely spaced than those of Transport, with less exaggerated tails on the

letters.

Been

based on Aksidenz Grotesk, Rail Alphabet does have a passing resemblance to

Helvetica, which was also based on Aksidenz Grotesk.

“It’s

ordinary, …. People think nobody designed it, because it’s ordinary.” – Margaret

Calvert

Like

Transport, its characters are designed to be made into tiles that can be scaled

to ensure correct spacing between letters.

Two

slightly different weights were made for better visibility. Rail Alphabet 1 (bigger)

for dark characters on bright backgrounds and Rail Alphabet 2 (smaller) for

light coloured characters on dark backgrounds.

Going

off Rail and out of UK

There

is some confusion on where Rail Alphabet was first used. Some say Rail Alphabet

was first used on NHS hospital signage, before first appearing in Liverpool

Street Station, London, in 1965. Others say it was the other way round. It was

later adopted by Belfast and Glasgow airports, before the British Airports

Authority adopted it for their airport signage in 1966. British armed forces even

adopted it for their signage. But it also found itself outside the UK. Jens

Nielsen used it in his redesign of the corporate identity of Danish State

Railways (DSB) in 1972.

Digitizing

Rail Alphabet

In

2005 a former student of Margret’s, Henrik Kubel,

and Scott Williams approached Margret the idea of

digitizing Rail Alphabet for a touring British art project. She agreed. Henrik

traced the original letterforms and produced a complete typeface in one weight.

It never got used in that project, but did get used in their catalogue Jane

and Louise Wilson for the QUAD exhibition in 2008.

Then,

in 2008, Margret got a call from a Spanish company wanting to make a version of

Rail Alphabet for a Corporate Client. She told them that it was already in the

process of digitalization, and renewed contact with Henrik.

It was

a huge task, made difficult due to its original sketches been scraped ages ago,

forcing Henrik to work with printed copies of British Airport specifications.

Then he discovered that the typeface Calvert was basically Rail Alphabet with

serifs, and used it as a base. “Now it is literally Calvert without serifs!” The

result was New Rail Alphabet, which comes in six weights, includes Eastern

European characters, and is available in italics. Originally called “Britanica”

it was released by A2 Type in 2009. These words are

written in New Rail Alphabet.

“I would say this is a very female version of a sans, it’s warmer than

Helvetica, it oozes Margaret in every detail. But my typefaces are very

feminine, so I think we complement each other very well. If you know that

Margaret did Transport as well, you see that it’s a natural way for her to draw

another sans, a more “Swiss” sans.” - Henrik Kubel

Rail

Alphabet Returns Home

Rail

Alphabet began to disappear on UK railway stations in the end of the 1980s,

when various branches of British Rail decided to rebrand. Then British Rail got

privatized in 1994, accelerating the trend. By the time Network Rail bought

control of the UK’s rail infrastructure in 2002, only trace amounts of Rail

Alphabet remained. In 2020, Margret and Henrik were commissioned by Network

Rail to design Rail Alphabet 2 for use on British railway stations.

Calvert

(Margaret’s namesake)

In

1977 Jock and Margaret worked on their last ever collaboration – creating the

identity for the Tyne and Wear Metro system in Newcastle. Been in an architecturally-interesting

city (and independent from British Rail) it was thought it needed a unique

typeface. That typeface was a reject from a previous project.

“The

typeface was originally designed in 1971 for the French new town of St

Quentin-en-Yveline as part of a much larger job, a report covering all aspects

of communication in the town. There was not much design in the report and the

typeface itself was not used as it was felt to be 'too English'. We felt it was

appropriate for Newcastle, where serifs would be an enriching element:

especially in stations such as Monument in the centre of the city.” - Margaret

Calvert (Frieze, 2003)

This

serif typeface made its first public appearance when the Metro opened in 1980.

In that same year, Monotype released it commercially and called it Calvert.

“I would never have chosen that name.” - Margaret Calvert

Comments

Post a Comment